Three Sovereigns For Sarah

TV REVIEW:

"VANESSA REDGRAVE AND SALEM WITCH TRIALS."

By JOHN J. O'CONNOR

Published: May 27, 1985

There are at least a couple of quite compelling reasons for watching ''Three Sovereigns for Sarah,'' a three-part American Playhouse series that begins tonight at 9 on Channel 13. Victor Pisano's script offers a clear and reasonable reconstruction of the Salem witch trials, one of the more odious and frightening events in American history. And the admirable production, steeped in authentic details, is illuminated by Vanessa Redgrave, giving another of her extraordinary dramatic performances.

Mr. Pisano has acknowledged his debt to ''Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft.'' Written by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, the book documents not only the religious but the social and economic factions that divided the Salem Village of Massachusetts in the last decades of the 17th century. In 1692, at the height of the witch hunts, Massachusetts actually lacked an official charter. There were no local magistrates, no written laws. The people were adrift.

Changing economic forces and family feuds were erupting. The notorious trials are seen growing out of fear, suspicion and jealousy. Religious hysteria was merely the weapon used in a tug of war between haves and have-nots.

The true story is told this time through Sarah Cloyce, played by Miss Redgrave. Sarah and her two older sisters, Rebecca Nurse and Mary Esty, were charged with witchcraft. Her sisters were hanged, but Sarah survived and later filed a petition to reverse the judgments against her family. That was in 1703, and that is when the drama begins as a frail and sick Sarah, one eye almost closed, is brought by her nephew to testify before a private court of the colony that is considering possible restitution to the families of those hanged for witchcraft 10 years earlier.

Sarah's recounting of ''the madness'' begins a few years earlier, in 1689, with the arrival in Salem Village of a new minister named Samuel Parris (William Lyman). His detractors argue that Parris is little more that a failed merchant from the West Indies who is demanding ''a small fortune from our hides.'' But he arrives, bringing his family and two slaves, whose voodoo practices will prove fatally attractive to some of Salem's children. In the end, Sarah will produce a map of the village and will show how a simple line drawn down the middle neatly divided the Parris factions and, not incidentally, the village's property disputes.

The hysteria begins with young girls, full of the promise of womanhood, being overwhelmed by some of their voodoo experiments. But instead of being questioned and reprimanded, they are protected by certain adults who themselves begin acting strangely. For the more impressionable, there is only one explanation. The evil hand is upon them. The village is bewitched. The accusations begin, with the names invariably coming from the adults, not the children. Hearings are organized. ''Spectral'' evidence is allowed. Innocence might be determined by such superstitious demands as being able to recite the Lord's Prayer without a single mistake. Sarah and her sisters are among 400 who will be accused and 150 who will be jailed. Twenty will die for their ''sins.''

This NightOwl Production, listing Benjamin Melniker and Michael Uslan as executive producers, has been assembled with admirable care. Authentic locations, Howard Cummings's production designs, and the photography direction of Larry Pizer (who has worked with Vanessa Redgrave on two previous films, ''Morgan'' and ''Isadora'') account for the film's splendid visual impact. And the cast, directed by Philip Leacock, is generally strong, from two lovely performances by Kim Hunter and Phyllis Thaxter as Sarah's sisters to smaller, but finely etched, contributions from Patrick McGoohan and Jenny Dundas.

Miss Redgrave is little short of phenomenal, her presence felt even when she isn't on the screen. She is clearly dedicated to the character of Sarah, a strong, forceful woman who is not cowed by the ordinary pressures for conformity.

While others wring their hands, Sarah looks at the lunacy around her and labels it tomfoolery. She may be silenced, but she will never be defeated. She clearly sees the nasty little self-interests hiding beneath the feverish piety. Thanks to Miss Redgrave's towering talent, the Salem witch trials once again become a vivid warning out of the troubled past.

This is the original house owned by "Goody" Rebecca Nurse which still stands on its original site and pedestal in Salem Village which is now known as Danvers, Massachusetts. The house, built around 1675, has its original russet color and most of the structure is original and still sound. The Rebecca Nurse Homestead remains one of the oldest dwellings in America and is open for public viewing. Rebecca Nurse was then in her seventies and one of three sisters accused of witchcraft by girls in her own village church. She is buried somewhere in an unmarked grave on the property.

Genealogical researchers and friends - check this site out: They're good people.

Authenticity

By Victor R. Pisano

writer/producer/educator

Three Sovereigns For Sarah

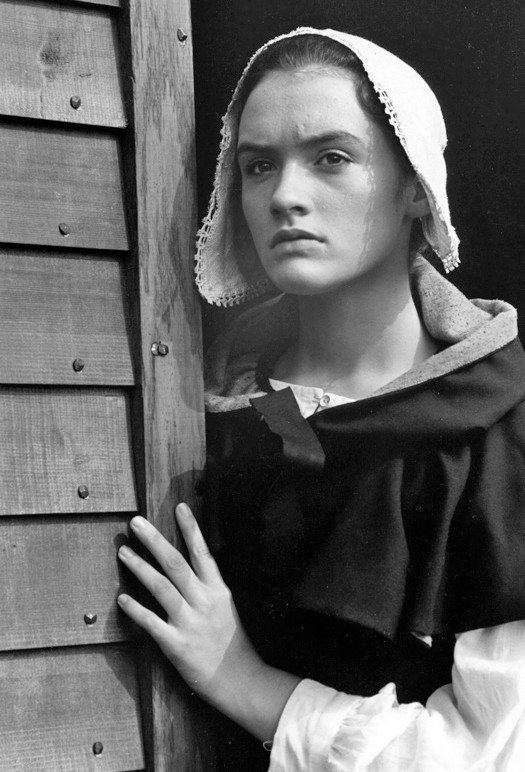

This black-and-white still for a production poster was taken on the Rebecca Nurse Homestead property in Danvers Massachusetts which was once called Salem Village. This is a real glimpse of exactly what it looked like in 1692 in Salem Village. The village was only eight miles from Salem Towne by the Sea where the Trials and executions took place.

We instructed our production Art Director, Howard Cummings, that we wanted to be able to turn off the sound of this PBS mini-series and to visually be able to experience what it looked and felt like in 1692 in Salem Village. Here, Vanessa Redgrave, portraying Sarah Cloye, stands in front of the Meeting House of Salem Village in a rare costume made of actual handwoven wool and linen of the period. There were 36 authentic costumes built for our actors - all constructed out of original materials. Our costume designer, Carol Ramsey, did extensive research to recreate these pieces of wardrobe. They now exist as the ONLY full set of representative clothing of this period (Period II) in existence made of original materials. The entire wardrobe is now housed and displayed in Salem, Massachusetts in the Essex Institute Museum of History.

Meeting House: This is the only structure of its kind in America. The Meeting House was both the Salem Village church and the Town Hall during this era. It was used daily for both functions. Our production company painstakingly researched the construction of the building which came from surviving church records and regional fragments. Noted local historian and town archivist, Richard Trask, meticulously oversaw this replication project. Wood shipbuilders from Boston were commisioned to construct the Meeting House. It was understandably solid and functional. Initially, we ran into a serious snag however when the building inspector of the modern town of Danvers rejected the re-construction plans as "not meeting local building code." We almost lost the production here and we probably would have without divine intervention. Thank you, Sarah. We fought for and received a waiver after a structural engineering company deemed the old plans "over and above" current code. Of course, they were.

Live Stock: Also in this production poster photo, are two "line-back" cows being tended by historian Peter Cooke of famed Plimoth Plantation in Plymouth, Massachusetts - a 1620, Period I, "living" museum in its own right. Peter informed us that this was the common livestock breed of the period before other varieties took over. At the time we took this still, there were only 16 line-back cattle in North America. These two were imported from Wales, UK, and cared for at the Plantation. Again - authenticity was paramount. The Oxen used in many scenes were also of a rare breed indicative of 1692 and cared for on Plimoth Plantation.

Fowl: In other scenes, Sarah and her sister Mary tend a group of chickens only found during the late 1600's - Dunghill chickens. no description needed.

Starting here, in the blend of this visual historical feast, you need only to add good acting, dialogue, and music. I am pleased to say that I received the largest grant in the history of the National Endowment for the Humanities based solely on my original screenplay, THREE SOVEREIGNS FOR SARAH. We shot the first draft and I continue to own the copyright to this wonderful production with a great partner in PBS - and Sarah and her sister's as well.

The TEACHER'S GUIDE will continue these observations in "freeze frame" throughout the three one-hour Episodes.

Victor R. Pisano IMDb Pro Info:

In the spring and summer of 1692, one particular family was at the core of the Salem Witch hysteria and subsequent trials - Thomas Putnam and his wife Anne. Their daughter Anne Ruth Putnam was one of the first afflicted girls of Salem Village. The hysterics began in the Village Meeting House when Anne Putnam Jr., and the minister's own daughter, Elizabeth "Bette" Parris, as well as the Reverend's live-in niece, Abigail Williams, all, came down with some manner of "fits." Some say it was the precociousness of the girls, others rightfully believed it was all a class struggle of the haves-and-have-nots of Salem Village. The girls were simply used as pawns.

Rebecca Nurse was sentenced to death by hanging in Salem Towne by the Sea. Rebecca was 71 years of age and the oldest of the three Towne sisters who grew up in Topsfield, Massachusetts in the mid-1600's. She was one of the first of the Salem Village Meeting House congregation to be accused by the girls of the village. History will preserve that Rebecca came to her property too quickly and she rose in rank. Rebecca Nurse was a commoner called "Goodwife" or "Goody" Nurse - only the wives of male property owners would be addressed as "Mrs." Because of this disparity and the property feuds in Salem Village, Rebbeca Nurse would ultimately hang due to those jealousies.

Sarah Cloyce, portrayed by Academy Award-winning actress Vanessa Redgrave, considers her defense as she herself is accused of witchcraft by the girls of Salem Village. Sarah was the youngest of three sisters, Rebecca Nurses, Mary Easty and herself - the Towne sisters of Topsfield, Massachusetts. Sarah, along with her sisters were accused of witchcraft. Sarah was the only of the three to escape the hanging tree. Sarah Cloyce principally relied on "the Good Book," the King James Bible, in her defense by relying literally on passages from Corinthians 3:16 "Know ye not that ye are the temple of God, and that the Spirit of God dwelleth in you? If any man defile the temple of God, him shall God destroy; for the temple of God is holy, which temple ye are."

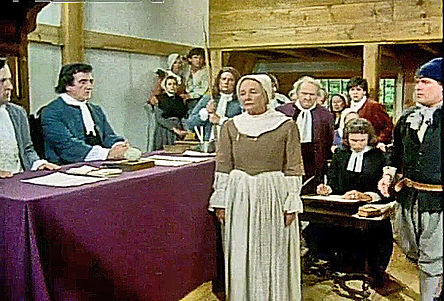

In this scene, village women confront Sarah just prior to her trial. They themselves wonder how far the accusations will travel. Most of the women in the village do not have the honor of formally being addressed as "Mrs." That was not permitted. They, like Sarah and her sisters, were called "Goodwife" or "Goody" and therefore were thought to be vulnerable to accusations by the more elite accusors and their daughters.

The High Sherrif of Salem territory, (portrayed by actor John Savoia) was responsible for rounding up those accused of witchcraft by the ever-growing number of adolescent girls of Salem Village. One of the accused, an old man named Giles Corey, was actually accused of witchcraft by his own wife, Martha. Martha turned her husband in after she was accused first. At his hearing, Corey refused to enter a plea of either innocent or guilty. In that era, by refusing to plea, one could not be sent to trial. So the court ordered the Sheriff to place Giles Corey on the ground under a large door-plank on which they placed heavy stones until Corey entered a plea. He stubbornly died three days later in defiance of the court and ultimately his accusatory wife. The last words Giles Corey spoke were - "More weight."

Elizabeth Hubbard, portrayed by actress, Rebecca Fasanello, was the niece of Dr. William Griggs, the village doctor who was charged with examining each of the afflicted girls who had contracted some manner of "fits." Elizabeth joined right in. Elizabeth was eighteen years of age in 1692 and the oldest of the girls. She became one of the leaders of the group and was close friends with Reverend Parris' own daughter Bette Parris and his niece Abigail Williams. Anne Putnam Jr. was another. These were the core girls of Salem Village who studied scripture hour upon hour every day along with domesticities in preparation for marriage - their ultimate and divine fate.

When those studies became interminably boring, as they understandably did, then the tight-nit girls of Salem Village came together to study at the Parson House near the Meeting House. Inside, during the dark winter of 1691, the girls took to taking their fortune with Reverend Parris' East Indian slave, Tituba (pronounced, "Tid-i-bah.") who was of Caribe Indian heritage. Tituba obliged the precocious girls who sought to know their fate - who they were to end up with as husbands - their most important question. This is where common boredom turned into caustic afflictions spawned by idle hands.

The impressionable girls were first given their future in the form of palm reading by Tituba. When this became mundane as well, Tituba turned to spontaneous fortune telling - Carribean style. She floated the whites of eggs suspended in water in a bowl. The eggwhites cast deformities in the reflected light of a candle - the bowl exploded in supernatural vision for each impressionable mind to gape at and to ponder. Not surprisingly, Reverend Parris nine-year-old daughter Bette, a sickly child to begin with, was the first to contract hallucinogenic fits - most likely due to Tituba's diversionary solution to boredom.

It all unraveled from there. The paranoic Reverend Parris and the incompetent Dr. Griggs, set in motion the beginning of the Salem Witch hysteria of 1692. These young girls of Salem Village were suddenly catapulted from the lowest members of the community to a group to be feared - almost worshipped. Why would they stop once they were empowered? Rhetorical question.

Tituba was the first to fall. When pressed hard, the girls of Salem Village named Tituba first as the culprit and "channeler" of the manifestations which befell the small village on the outskirts of Salem Towne by the Sea. Soon after, names of other villagers came to the lips of the hysterical and untethered girls. Old vagabond women at first. Then, prominent detractors of the girl's families - political and religious adversaries alike - even the past minister.

Thus began and became - the Salem Witch hysteria and subsequent Trials of 1692.

Below, actor Christopher Childs portrays the Most Reverend Mister Nicholas Noyse, minister of Salem Towne by the Sea in 1692. That was a minister's full title during the Calvinist rule of that era. Likewise, his counterpart, the Most Reverend Mister Samuel Parris ruled the Meeting House in nearby Salem Village where the hysteria first broke out. Interestingly, Reverend Parris' young nine-year-old daughter, Elizabeth "Bette" Parris was to become the first of the afflicted girls along with his live-in niece Abigail Williams. This corroborates the prevailing belief that the Salem Witch Trials were due, in most part, to an early outbreak of church politics and female children who held the lowest social position in the village - or anywhere else. The adolescent girls became emboldened and climbed from the bottom to the top of the social ladder in influence.

Reverend Noyse was the "hanging" minister present at the hangings of those accused of witchcraft. The accused were tied, bound and carried to the top of a ladder. Noyse would proclaim his condemnation and the hangman would then "roll" the convicted off and hanged. The convicted witches more than likely died of asphyxiation from strangulation as opposed to a broken neck. One accused witch named Sarah Goode, a poor destitute young woman was reputed to scream out to the Minister Mr. Noyse before she was rolled off the ladder: "If you take away my life - God will give you blood to drink!"

Several years later, it was found in public record, that the Most Reverend Mister Nicholas Noyse, died of an internal hemorrhage - and did indeed die, "drinking his own blood."

Coincidentally, Elizabeth Hubbard, Dr. Griggs' niece, was also a best friend and a cohort to Anne Ruth Putnam Jr., the eldest daughter of Thomas and Anne Putnam Sr. The Putnam family of Salem Village were fighting hard to keep their own property intact and were alarmed to see it all be broken up and taken away through family inheritances and people they considered less than worthy interlopers. Doctor Griggs was the village doctor who examined all of the afflicted girls and had no medical explanation for their "fits." Dr. Griggs surmised that, "The evil hand was upon these children." His niece, Elizabeth, openly advanced that misdiagnosis.

Thomas Putnam had an official title of "Mister" and his wife was properly called "Mrs." Anne Putnam. And who were those who came up too quickly with land and possession? "Goody," Rebecca Nurse and her sisters, Mary Easty and Sarah Cloyce. The historical jigsaw puzzle of church politics and bad blood amongst neighbors is easy to reconstruct.

In this scene above, Elizabeth Hubbard visits her friend Anne Putnam Jr. (portrayed by actress Jennie Dundas) and together they inspire each other to fall victim and to perform the hysteria in front of a helpless Thomas Putnam (portrayed by actor Daniel von Bargen). It's hard to tell if the girls are truly "possessed" or egging each other on - most scholars believe a little both.

Thomas Putnam looks on helplessly as his oldest daughter and Dr. Griggs' own niece carry on with all manner of fits. When the girls yell out, "We are being pinched and beaten!" "See! Don't you see them, Father? There! See?" Spectral evidence. The stricken Thomas Putnam confides he sees nothing and seeks divine intervention. The girl's answer his prayer and his demand to name names. And the names they chose? Those whom the Putnam family are feuding with within the village church and over land disputes.

Rebecca Nurse is among the first names that came to mind for these "innocent" girls.